Alfa Mist - Live at Real World Studios

-

Music

-

Music

On Roulette, his sixth studio release, the prolific producer, songwriter, pianist and MC Alfa Mist created a vivid sci-fi universe — a vast dystopia shaped by themes of revenge, forgiveness and redemption. Now, that world is brought into sharp focus in a new video capturing Alfa Mist performing tracks from the record live at Real World Studios.

Filmed in the renowned Wiltshire studio complex, the performance strips Roulette back to its emotional core while amplifying its conceptual weight. Alfa Mist’s music has always grappled with big ideas, but here those ideas feel immediate and embodied. Roulette imagines a near-future where reincarnation is discovered to be real — a force connecting dreams, past lives and accumulated knowledge — raising urgent ethical, moral and philosophical questions. In this live setting, those questions resonate with renewed intensity.

Across the performance, Alfa moves through selections from the album as if spinning the wheel once more: each track revealing a different character, mood and perspective. His unmistakable signature remains — lambent piano lines, intuitive grooves and moments of free-flowing jazz improvisation — but in the acoustics of Real World Studios, the music takes on a deeper, more cinematic presence. The smoky psychedelia of Roulette feels immersive and tactile, designed not just to be heard but fully felt.

The video also highlights some of Alfa Mist’s most ambitious arrangements to date, including passages that glide effortlessly through shifting time signatures. “Life’s not always linear,” he has said — a philosophy that plays out vividly in the fluidity of the live performance.

This Real World Studios session underlines Alfa Mist’s position as one of the most forward-thinking composers in UK music today. With melodies that linger long after the final note, the performance captures an artist in constant evolution. As Alfa puts it: “Music is a constant; it’s my state of mind that I keep chiselling and working on.” In this filmed performance, that process is visible, audible and deeply compelling.

He performs in Amsterdam at Paradiso on Wednesday, January 28th. Tickets are available now.

Related Articles

-

The Alchemist presents episode three of their tour vlog, Amsterdam edition. Watch now.

The Alchemist presents episode three of their tour vlog, Amsterdam edition. Watch now. -

Get Familiar: ARTNOIR

Get Familiar: ARTNOIR

Interview by Passion Dzenga | Photography by Pebbles BazurARTNOIR is a community first and an institution second — seven co-founders building the kind of art world they wanted to exist in, then inviting everyone else into it. Since 2013, they have used the platform to amplify Black and Brown creatives across disciplines, not just through exhibitions and walkthroughs, but through real infrastructure like Jar of Love: a micro-grant that has redistributed resources to artists and cultural workers when the bigger systems proved fragile.Now, ARTNOIR makes its Dutch debut through a collaboration with OSCAM in Amsterdam Zuidoost — a meeting of two Black women-led institutions that understand the power of place, and the urgency of showing up for community in real time. Their joint exhibition, Watering a Black Garden, lands during International Women’s Month and brings together eight women and non-binary artists from across the diaspora, reframing joy as something intentional: tending, care, rest, and becoming. In this conversation, Larry Ossei-Mensah and Carolyn “CC” Concepcion, co-founders of ARTNOIR, unpack how the show came together, why “radical joy” is a necessary lens, what sustainability actually looks like behind the scenes, and how they’re extending the exhibition beyond the gallery walls — into workshops, circles, and even a book list at the OBA, so visitors can take the experience home.For readers who are just meeting you: what is ARTNOIR - and why bring ARTNOIR to the Netherlands to partner with OSCAM now?Larry Ossei-Mensah: ARTNOIR is a collective platform. We started in 2013, formally it’s seven of us as co-founders and it stems from wanting to create the world we want to see. At the time, we recognized there were a lot of emerging artists doing incredible things but not getting engagement from our generation of patrons. For example, there were curators doing amazing work but not getting the support they needed. A lot of what we’ve done has been about amplifying the voices of Black and Brown, Latin, Latinx, Asian creatives — primarily visual artists but we’ve also worked with writers, dancers, musicians.One example is our Jar of Love microgrant, which we started in 2020. One of our grantees, Samora Pinderhughes, just had an exhibition at MoMA, Call and Response. He presented a new video piece and did a number of performances — and to be part of that journey has been really fruitful and rewarding. When I started working in the arts back in 2008, there were maybe a couple galleries showing Black artists. And now we’re in institutions consistently - but even within that, how do we show up and for each other?We do exhibition walkthroughs and we support exhibitions. We supported the British Pavilion for John Akomfrah’s presentation in 2024 and we’re supporting the British Pavilion again this year for Lubaina Himid's presentation. Since 2013, we’ve understood the importance of the platform being international, not just focusing on the United States. We have delivered projects in South Africa in collaboration with Black Portraiture, partnered with the U.S. Embassy in Paris, and worked in London with Samuel Ross and SR_A on the Black British Artist Grant.In terms of Amsterdam, OSCAM reached out to us to explore what a collaboration could look like. Marian Duff is the founder, and we’ve been working with Annicée Angela, who’s co-curating, and Manu Drenthem Soesman, who’s been helping with production. OSCAM does really important work. When they reached out, I hit up my people in Amsterdam: “Tell us more about OSCAM and its role, and everyone we spoke to emphasized the importance of OSCAM and the work they do.”. I’ve had the opportunity to spend meaningful time in the Bijlmer, which has given me a deeper understanding of what the neighborhood represents within a broader social and cultural context. I see art as a vehicle for conversation, specifically through this project, Watering a Black Garden: Reimagining Joy as a Radical Act of Tending and Becoming, and in considering what it means to present a group exhibition of Black and Brown women and non-binary artists.The timing is also intentional: International Women’s Month. The exhibition is celebrating the month, platforming these voices and artistic expressions, and being in dialogue with the creative community in Amsterdam. I’ve been visiting Amsterdam for the last 20 years, so my network is vast - people in fashion, visual arts, and everyday folks who live there. How can we collaborate, bring our flavor, and bring communities together?We’re not under the assumption that because Amsterdam is “small,” there isn’t an opportunity for engagement and dialogue. I always think about how, in New York, you need special moments that invite people to come out, especially after people have been hibernating, and with the weather getting better. It gives people a reason to pull up — especially if they live in other parts of the city — to say: “We’re going to go to Zuidoost, support this exhibition, see what these artists have to say, support the programming.” And also support OSCAM's work.We are always trying to identify mission-aligned partners who are changing the narrative, expanding discourse, and building a platform that’s accessible not only to creatives but to everyday folks. I did a site visit to OSCAM in October and it was great to watch the aunties coming from the grocery store popping in just to say hello. This is a really important component, community has been a bedrock for what we do regardless of where in the world we show up and collaborate.Carolyn “CC” Concepcion: I’ll add to that: community is central for us. We serve two constituents. We serve the artists — creatives, curators, culture producers, designers, makers — and we also serve communities of color that are interested in the arts. Accessibility is central to our mission. How do we invite our people into institutions, into gallery walls, into art and culture environments that can be intimidating and aren’t designed or programmed with them in mind?That’s why the field trips and walkthroughs are integral to how we got started — it was friends who wanted to see themselves in the art world, and they wanted to see it together. They wanted permission, inspiration, and to not be intimidated. If you like art — if you have even a mustard seed of interest — we can give you a path: where to go see it, how to see it. If you’re interested in collecting, we can support you with entry points. It’s about why you belong in the space, and highlighting who is creating with your narrative at the center.Watering a Black Garden brings together eight female and non-binary artists across disciplines. How did you build that list, and what threads connect their practices for you?Larry Ossei-Mensah: It’s a combination. Some are artists we’ve been following for a long time and really admire. We did research. Once we agreed on the prompt — focusing on platforming the women of colour — we were also thinking about diaspora. We wanted, to the best of our ability, to represent different voices and perspectives across the diaspora.Aline Motta, for example — Afro-Brazilian — I’ve gotten to know her over the last several years through projects in Brazil. Shaniqwa Jarvis is an incredible photographer and artist, and also a friend. It’s been amazing to witness her journey — and to find the right fit and the right timing to share her fine art practice alongside her commercial photography practice.Nengi Omuku is someone I’ve gotten to know over the last several years — I’ve shown her work before at the ICA in San Francisco. Same with Ufuoma Essi; this might be the secondtime I’ve engaged with her practice, having shown it at the MET in Manila, Philippines. Jennette Ehlers, I had been following and met last year while on a trip to Copenhagen, facilitated by the Danish Foundation. We wanted diversity in perspectives and mediums. We think about the exhibition at OSCAM as the soil — what grows from that soil are these varying expressions and ideas. So it’s been great: artists we know, artists we’ve researched, artists we feel have something to say — and we’re excited to collaborate with them. We have artists from Brazil, the U.S., Congo — Copenhagen, Nigeria, UK, France, and the Caribbean - our diaspora moves around, and we want those perspectives highlighted.Carolyn “CC” Concepcion: And another entry point to finalizing our artist list is OSCAM’s focus on emerging artists and young creatives of color. So we also looked to artists — like Rachel Marsil from Paris, Maty Biayenda from Paris, Bernice Mulenga from London — young, electric, vibrant artists at an inflection point in their careers. They have so much more to go and being part of their journey, helping expand their audience and impact, is inspiring. Larry Ossei-Mensah: So much is about the journey. The Venice Biennale just released the list of participating artists, and a number of them are artists we’ve supported in various forms. It might be romantic for me, but knowing you played a small part in helping them get to what they’re destined to get to — that’s powerful.And I believe most of these artists are showing in the Netherlands for the first time. There’s still a lot of work to do in terms of visibility for artists of color, platforming artists of color. This is showing up boldly, unabashedly, with love and care.A lot of the time, Black art gets framed through suffering and trauma. How do you present Black work without defaulting to that lens, while still being honest about the diasporic experience?Larry Ossei-Mensah: That was the intention from the beginning: to illustrate a different and more expanded point of view. It’s part of the journey, but it doesn’t have to be what we’re always centering.We’re thinking about joy, but not in a stereotypical “happy-go-lucky” way. Joy as tending. What does it mean to care for oneself and one’s community? Women and non-binary individuals are often the ones who feed our souls, minds, and spirits. We also wanted to complicate it: joy as intentional choices, how you hold space, how we hold space together, regardless of circumstance. This journey toward freedom, possibility, imagination — there’s no endpoint. It requires consistent engagement and dialogue, finding pockets of respite regardless of what’s happening.There’s always something happening in the world — to varying degrees. So, be mindful, but also look at ourselves, look at each other. Highlight the breadth and depth of what makes us human — complicated, layered, multi-faceted — and in the case of the exhibitions, using different forms of media. Centering wholeness was important in shaping the exhibition and selecting artists.Even the programming extends this. We’re partnering with the OBA Bijlmerplein near OSCAM — putting together a reading list. What does it mean to find a bell hooks book that allows you to process what’s happening in the exhibition? That extension is unique and exciting.Carolyn “CC” Concepcion: I’ll add to that by speaking on the title and the programming. The title Watering a Black Garden came to us after I revisited a photograph I took in 2024 of Raymond Saunders’s work at David Zwirner Gallery during Post No Bills, an exhibition curated by Ebony L. Haynes. Across a Black canvas “Watering a Black Garden” was written.. It felt rooted, powerful, magical. I posted it on my IG stories,Larry saw it, and said: “Oh my god, that’s the name of our exhibition in Amsterdam.” He was like: “I think that’s it.” Our good friend Ebony Haynes, Global Head of Curatorial Projects, further educated us on Saunders' work and what the garden meant to him, and it solidified things for us. So we honor these legends — the artists who laid the foundation. Raymond Saunders is centered and honored in when we speak about where the title of this exhibition came from.And in regards to joy: the programming is intentional. Bernice is coming to do a workshop around her photography practice. We’re doing a flower bouquet-making workshop — touching nature in real life. We’re doing a gathering with Up Close — part of the Amsterdam community — centered on healing circles. It’s wholesome: centering Black legends and centering women across the diaspora.ARTNOIR is a predominantly Black and Brown women-led organization — five women — so uplifting Black and Brown women artists is front and center. And OSCAM is also Black women-led and founded. So it all made sense.Larry Ossei-Mensah: From our research and observation, that’s where both organisations dovetail: pouring into our community, through exhibitions, programming, and even just being a space where “aunties” or “cousins” can come in and say hello. When I did my visit, I noticed it’s a vibe on multiple levels.The title encapsulates the idea: we have to keep pouring into each other regardless of what’s happening — sometimes in spite of what’s happening — to give ourselves the strength, the vision, the imagination to keep moving forward collectively.You’re building something that’s sustainable — and sustainability usually means you’re also thinking about burnout, rest, and care. How do you create space and respite inside the work, especially when this becomes a transatlantic diasporic conversation?Larry Ossei-Mensah: Definitely. It’s a constant process of evolution. It has different faces. For example, when we do our women’s dinner — usually biannual — it can look different. Last year, we did a ceramics workshop, and the year before, it was at the studio of our good friend Asmeret Berhe-Lumax, the founder of One Love Community Fridge. We are constantly mixing the approach to how we engage our community: field trips, going to see art, breaking bread and sharing a meal, and exchanging ideas. And physical, tactile moments — slowing down — is where a light bulb might go off.That’s partly why the programming has landed where it has. It’s one thing to say: “Come see the show, come do a tour.” It’s another to have an artist workshop guide us through lens-based practice — documenting community, telling stories, building an archive. Or to do a flower-arranging workshop — it might seem simple, but we’re all busy, we’re all programmed. So, saying - stop for an hour or two, focus on yourself, focus on community, bring a friend, share time - is helpful.Coming out of COVID, people are more hyper-alert to what’s sustainable. This is a long fight and journey toward freedom or liberation — a holistic approach to living. Our communities — especially if you’re first-gen — hard work and sacrifice are embedded in our psyche. That is important, but so is enjoying life, enjoying friends, having space to dream. The pressure is intense.Even reading a book shouldn’t be a luxury, but for some people it is. Taking time to read Toni Morrison and feed your mind, that matters. So we try to be intentional and strategic with how it shows up in our work.I co-curated an exhibition at Storm King (with Nora Lawrence & Adela Goldsmith), a sculpture park in upstate New York, of Sonia Gomes' work last year— and bringing people into a landscape, showing work, having a performance — it’s a reset. While living in a big city, those reminders are important.And there’s also a benefit in having seven co-founders, mixing and matching when needed. When someone steps back, someone else can take the baton and move things forward.Carolyn “CC” Concepcion: I wanted to speak to the shadow side: burnout, labor, and what it actually takes to build something like this. We’re seven co-founders, but none of us take a salary. We have a small but mighty team of interns and fellows who keep the engine going. We all have full-time jobs. We have kids. We have parents — aging parents. We have partners. And we make a choice every day to do this work for ARTNOIR — to make this space for our community. It’s intentional, curated, selected. And yes, it burns us out sometimes. Institution building for our community — resources aren’t always available. So we have to be scrappy and chic all the time, on a nonprofit budget.And especially in this climate — Black History Month is every day for us. DEI is not a checkbox; it’s our life. In this new administration — it’s more challenging to be loud and proud, but also to stay on the low with the work so we’re not targeted. That’s a new reality. Burnout isn’t just “wellness”; it’s also the pressure of leadership and visibility.Patta is doing this work too — you’re just using a different lens — but it’s all culture-making: image-making, object-making, archival work, storytelling of the Black experience. That’s the shadow side of building in service to our people.Jar of Love is one of the infrastructural pieces that really stands out. Can you break down what it is, how it works, and what resource redistribution and care look like in practice?Larry Ossei-Mensah: Jar of Love emerged from a practical use case. During COVID, once we understood what was happening, I noticed colleagues being furloughed, laid off — and you saw these “mighty” institutions were basically built on wooden stilts. On top of everything happening in the world — George Floyd, etc. — we asked: how do we support from where we stand?So we decided collectively: how can we re-grant or create mutual aid for colleagues in a dire moment? We started the fund in 2020 in partnership with several artists. We did online auctions with Artsy, with the support of then-CMO Everette Taylor — now CEO at Kickstarter — and raised funds. Then we held an open call for a non-restricted microgrant: $500 to $3,000, depending on need.Since 2020, we’ve reinvested over $350K in more than 150 artists, curators, cultural workers, and filmmakers. Initially, it was “for the COVID moment,” but even after that, we still saw the need. It’s an infrastructural gap.We’ve partnered with Sotheby’s, with the support of Walden Huntley-Fenner, and moved to a cohort model. Now we bring in a group of six or seven and try to create a network effect. With the recent cohort, it becomes not just funding, but convening: a filmmaker meets a musician — can you do a score? It becomes an ecosystem.We still provide resources for dream projects and needs, but now we’re asking: what does professional development look like? What do people need now? What are you working on that we can amplify? How else can we support — emotionally, with introductions, and by showing up? And it’s satisfying to see grantees hit their moments. Watching it manifest is one of the most satisfying feelings. We keep evolving it to meet the moment — needs change — and our superpower has been our adaptability and nimbleness.Carolyn “CC” Concepcion: It’s about being responsive when people need it most. COVID was the impetus, but it continues. We expanded Jar of Love in LA during the LA fires — distributing funds aligned with how we did it during COVID. Artists have studio fires, lose parents, get sick — that drumbeat continues, alongside the cohort model.Funding looks different across countries. London isn’t as generous as the U.S. in cultural funding. Our $5,000 might not be “that much,” but it’s the intention: we see you. It’s not only financial — it's the community seeing you and supporting you at different stages.Our goal is to expand in Paris. Our goal is to expand in Amsterdam. That’s something we can work on together — finding the funds — especially in centers of creative exchange tied to the African diaspora.Let’s get practical: what’s the full rundown of programming around OSCAM? Key dates, key moments — what should people pull up for?Carolyn “CC” Concepcion: March 6th is press and VIP programming. Miss Sunny will DJ and Sylvana Simons will do the welcoming — she’s very loved in Amsterdam. We’ll have a panel with fourof the artists who are in town. For the opening, we have more DJs: Princess Vineyard is coming, and then there’ll be an afterparty with AK SoundSystem — so it’s going to be kind of lit. A lot of music, a lot of vibes.The caterer is Tabili, two sisters doing beautiful work inspired by different parts of the diaspora: Brazilian food, Caribbean food, food from the continent all on the 6th.Then the other programs run between March and April: programming with Up Close and the library, an art workshop with Bernice Mulenga, and the flower-making workshop. And the book selection — when does that hit the OBA?Larry Ossei-Mensah: It will launch during the opening of the exhibition. At OBA Bijlmerplein, we will have an area with books, a flyer, and materials with QR codes. The book list will also be online.We’re also doing a playlist. It’s about extending the exhibition and letting people bring it home. You see an incredible painting by Rachel Marsil, you’re moved, then you stumble into an Audre Lorde book that invites you to think about what it is to be a person of color in repose.The first time I came to Amsterdam, a buddy lived by the Heineken factory and said, “Let’s bike to the park.” I was 24, from the Bronx — I was like, “What?” Watching people picnic, relax, and be at rest - that was strange for me then. If I went to the park, it was to play basketball, not to rest.So to have a visual representation of your body at rest — not in fight-or-flight — and then literature or music that can support what you feel as you move through the show: that’s an essential part of making it holistic.Watering a Black Garden is curated by Annicée Angela (OSCAM), Carolyn “CC” Concepcion & Larry Ossei-Mensah (ARTNOIR) and will be on view at OSCAM, Bijlmerplein 110, 1102 DB Amsterdam from Friday, March 6th to May 6th, 2026.-

Art

-

Events

-

-

Get Familiar: Jerrau

Get Familiar: Jerrau

Interview by Passion Dzenga | Photography by Liesje Verhave and Pebbles BazurOver the past few years, Jerrau has quietly but confidently carved out his place as one of Amsterdam’s most versatile and forward-thinking DJs. Effortlessly moving between breakbeats, bass-heavy club sounds, alternative electronic hip-hop and soulful house, the Surinamese-Dutch selector has built a reputation for sets that are hard to categorise but impossible to ignore. Whether he’s closing at Lowlands, holding it down in the club at De School, performing at Down The Rabbit Hole with Erykah Badu on the mic or showing us the way during his Patta x Keep Hush session, Jerrau’s approach has always been rooted in curiosity, culture and an instinctive understanding of the dancefloor.Now, after years of refining his voice behind the decks, he steps into a new chapter with his debut EP, It All Starts With This, released on Who’s Susan. A project shaped by discipline, mentorship and a deep love for bass lineage — from Amsterdam to the UK and beyond — the record marks a deliberate beginning. Inspired as much by Sonic soundtracks as by sound system pressure, Jerrau’s move into production feels less like a pivot and more like a natural extension of the world he’s been building all along.We caught up with him to talk about finally committing to the studio, learning to let go during a month-long residency in Nicaragua, his unexpected place within the Black British music ecosystem, and why, whether DJing or producing, the room always comes first.Jerrau is wearing the Patta 3M Reflective Waterproof Rain JacketThis will be your first release after years behind the decks and you have mentioned that you have “flirted” with producing for years, what shifted for you to take it more seriously now?I’ve always been curious about producing and I’ve picked it up a few times over the years, but it never really stuck. I’d dive in, get excited, then I would feel overwhelmed by how many possibilities there are and then life or DJing would pull me back out of it. It was always there in the background though.What really shifted things was when Tsepo, offered to teach me. That felt different. There’s this “each one, teach one” mentality — almost like that Black Panther ethos — and when he reached out, it felt like a moment I wasn’t supposed to ignore. We only had a couple of sessions together but it was really a turning point for me. I took that as a sign that it was time to stop flirting with the idea and actually commit. So when starting this journey, next to the few sessions I had with Tsepo. My friend Tijn also just started making music and for the first few months we went to the studio together all the time just to try to get better and learn from each other.I sometimes think I should have started during the pandemic when there was more time and space to focus, but I’ve realised you don’t find time — you make it. Over the past 18 months, I’ve really treated it seriously: I got access to a studio here in Amsterdam, put in the hours, and approached it with the same discipline I’ve brought to DJing. That consistency is what’s made the difference.The title, It All Starts With This sounds very intentional. What does “this” represent in your musical journey right now?The title actually comes from one of my favourite games, Sonic Adventure 2. I basically have all the dialogue from that game burned into my head. I’m honestly not the best at naming things — even my DJ name is just my actual name — so titling tracks and projects has always been a bit of a challenge for me.When we were finalising the selection, the artwork and the sequencing for the record, that dialogue just kept coming back to me. It felt simple but loaded. It didn’t feel forced or overly conceptual — it just felt right.For me now, “this” represents the starting point. It’s the first proper step into producing, into putting something out that’s fully mine. It’s not necessarily about having all the answers — it’s more about committing to the beginning.Jerrau is wearing the Patta Track Top CardiganHow has your journey as a DJ influenced your approach to producing — and has producing changed the way you DJ?DJing has definitely influenced the production more than the other way around. Years of being on the dancefloor and in the booth teach you what actually works in a room — how tension builds, how long a groove needs to breathe, when to strip things back, when to push. That experience naturally informs how I approach making a track. I’m always thinking about how something will translate physically, not just how it sounds in the studio.Producing has influenced my DJing in a more subtle way. I’ve had to think more carefully about how my own tracks fit into my sets — where they make sense, what they sit next to. But I’m never going to brute-force my own music into a set just because it’s mine. DJing and producing are different practices, and they should be treated that way. For me, the room always comes first. If one of my tracks serves that moment, great. If not, that’s fine too.At the same time, I still feel like I’m learning, and there is a lot to learn. One area I really want to deepen my understanding of is mixing and mastering. I want to understand that final stage of the process properly — not just creatively, but technically — so I can have even more control over how the music translates, both in the club and beyond.Why did you choose to work with Who’s Susan?Who’s Susan is just a really dope label. Over the past few years, I’ve bought pretty much everything they’ve released. I’ve always respected their curation and the world they’ve built around the music.It actually happened quite organically. I was promoting one of my own nights and used one of my demos as the audio for a post. Willem from the label heard it and reached out to ask if I had more material. He connected with the direction I was exploring and felt it aligned with what Who’s Susan was doing. That meant a lot, because it didn’t feel forced — it felt like a natural fit on both sides.That alignment made the decision easy. And it feels full circle in a way — the one feature on the EP is from one of their legacy artists, DJ OSX, formerly known as DJ Windows XP. So to go from being a supporter of the label to releasing on it, and collaborating within that family, feels really special.The artwork for your debut EP aesthetically reminds me of one of your big inspirations, Sonic, was this intentional?Interestingly, the artwork was actually made before we fully put the record together. So it wasn’t a case of me saying, “Let’s make this look like Sonic.” It was more organic than that. Sjon de Baron, who does all the artwork for Who’s Susan, really understands me and what I’m about. He was able to translate the feeling of the music visually, while still keeping it consistent with the label’s wider art direction. I think that’s why it resonates in that way — it reflects my influences without being literal. There’s definitely a shared visual language there, but it came from mutual understanding rather than a direct reference.You traded Amsterdam for a month in Nicaragua at Popoyo’s Secret. What pulled you there, and how did a residency format change your approach compared to festivals or single-night gigs?What really appealed to me about Nicaragua was the idea of stepping outside my usual rhythm. Amsterdam can be intense — fast-paced, scene-driven, and very plugged in. Spending a month somewhere more remote, surrounded by nature and a different energy, felt like a chance to reset.I ended up loving it. I’d go back in a heartbeat. There was something really refreshing about being there — it stripped things back in a good way. The residency format was also very different from a festival or a one-off club set. I tend to approach DJing almost like programming — thinking carefully about structure, context, and what makes sense for a specific slot. During the residency, I played at different times of day, so each set required a different mindset. You can’t approach a sunset set the same way you approach a late-night peak-time slot.What I really enjoyed, though, was the freedom. Being in the same place for a month allowed me to build a relationship with the space and the people. I felt less pressure to prove something and more space to just have fun. I think I let go of a slightly more “pretentious” side of DJing — that idea of only playing very specific records to signal something. It became more about what felt good in the moment. That shift was probably the biggest takeaway.Being a devoted Chelsea supporter, do you feel your connection to the UK through football has influenced your relationship with UK music? And where are you hoping to head next?I was actually living in the UK for my first few years on this earth, Surrey to be exact. It’s funny — the last time I was in the UK for a show, I visited a museum exhibition about the history of Black British music. I was watching one of the video installations and saw this quick flash that looked like me. I kept watching and realised it actually was me — they had included footage from my Patta x Keep Hush set in the exhibition.That was a surreal moment. It made me realise that my connection to the UK scene isn’t just from a distance — in some small way and it was cool to be included in the Black British music ecosystem. I’ve always felt drawn to the UK, not just because I’m a Chelsea fan, but because of the depth of its bass music culture. There’s such a strong lineage of sound system energy and low-end pressure that really resonates with me. That influence definitely shapes how I think about rhythm and space in my own sets. I’d love to spend more time in places like London, Bristol and Manchester — cities with deep bass traditions and strong musical identities. And of course, making it to Stamford Bridge for a Chelsea game is still on the list too!Ready to hear the next step? is out now via Who’s Susan — press play and start the journey with Jerrau. It all starts with this by Jerrau-

Get Familiar

-

-

OSCAM and ARTNOIR Present 'Watering a Black Garden'

OSCAM and ARTNOIR Present 'Watering a...

A Transatlantic Exhibition Centering Joy, Lineage, and the Creative Sovereignty of Women of Color at OSCAM (Open Space Contemporary Art Museum), AmsterdamMarch 6th to May 6th, 2026Eight women and non-binary artists from across the African diaspora, based in six countries, come together in Amsterdam to affirm joy, presence, and flourishing as radical and necessary acts.On March 6, 2026, OSCAM (Open Space Contemporary Art Museum) and ARTNOIR present Watering a Black Garden, a group exhibition that reimagines joy as a radical act of tending and becoming. Centering Black and Brown women as visionaries of abundance, the exhibition frames joy as an intentional and sustained practice of care within Black femme experiences.This landmark exhibition marks a powerful transatlantic collaboration rooted in shared commitments to equity, visibility, and cultural exchange. The exhibition features work by Maty Biayenda, Jeannette Ehlers, Ufuoma Essi, Shaniqwa Jarvis, Rachel Marsil, Aline Motta, Bernice Mulenga, and Nengi Omuku.Connecting New York and AmsterdamWith this collaboration, ARTNOIR makes its debut in the Netherlands, forging a cultural bridge between New York and Amsterdam. A female-majority, Black- and Brown-led platform, ARTNOIR supports artists of color through exhibitions, partnerships, and global storytelling.Together, OSCAM and ARTNOIR expand access, visibility, and opportunity within the contemporary art world, bringing underrepresented voices to the forefront. The partnership connects local audiences with global conversations while positioning Amsterdam-Zuidoost on the international cultural stage.Joy as a Sustained PracticeWatering a Black Garden takes inspiration from a seminal painting by Raymond Saunders, which bears the phrase “watering a black garden” written across a black canvas. The painting serves as both metaphor and call to action for the exhibition’s curators.The exhibition asks: What does it mean to nurture oneself, one’s community, and one’s creative lineage in a world shaped by histories of erasure and ongoing inequity?Through diverse artistic practices, “watering” becomes a metaphor for ongoing, intentional acts that foster flourishing. The garden emerges as a site where memory and lineage are nourished and alternative futures take root. Rather than functioning as a passive backdrop, the garden proposes a way of being—grounded, attentive, and expansive.The richness of the exhibition reflects the fullness of Black and Brown femme life, where radiance is essential rather than decorative. Across disciplines, the artists assert presence as both a personal and political act, resisting invisibility while opening space for healing, connection, and becoming.Marian Duff, Founding Director of OSCAM, shares:“This collaboration feels both natural and deeply meaningful. I have followed ARTNOIR for many years, and I am proud that together we are bringing artists from around the world to Amsterdam-Zuidoost for their Dutch debut.”Larry Ossei-Mensah, Co-founder of ARTNOIR and co-curator of the exhibition, adds:“Watering a Black Garden is both an offering and an insistence. It creates space for women of color to be fully present—joyful, complex, and sovereign. The works in this exhibition remind us that flourishing itself is a form of resistance.”Eight Artists from Across the DiasporaThe participating artists embody this ethos across diverse disciplines and cultural contexts:Maty Biayenda (FR) interrogates the erasure of African narratives in European discourse.Jeannette Ehlers (DK/TT) confronts colonial histories through processes of healing and repair.Ufuoma Essi (GB/NG) explores Black feminist epistemologies and collective memory through video.Shaniqwa Jarvis (USA) captures vulnerability and optimism through photography.Rachel Marsil (FR) reimagines embodiment and identity through performance.Aline Motta (BR) traces familial histories disrupted by colonial violence.Bernice Mulenga (GB/DRC) examines intimacy within the self and the Black queer community.Nengi Omuku (NG) creates immersive worlds reflecting place and belonging.-

Art

-

-

SALIMATA - Jackpot & Foil

SALIMATA - Jackpot & Foil

SALIMATA brings Brooklyn bravado and fearless wordplay to the COLORS stage with a razorsharp performance of ‘Jackpot’ and ‘Foil’, from her latest album ‘The Happening’.-

Music

-

-

PLOEGENDIENST - SURINAAMSE BROODJES

PLOEGENDIENST - SURINAAMSE BROODJES

Ploegendienst drops new single “SURINAAMSE BROODJES”. Ahead of their upcoming album "GEEN TITEL" and 2026 live tour. Pre-order "GEEN TITEL" now.-

Music

-

-

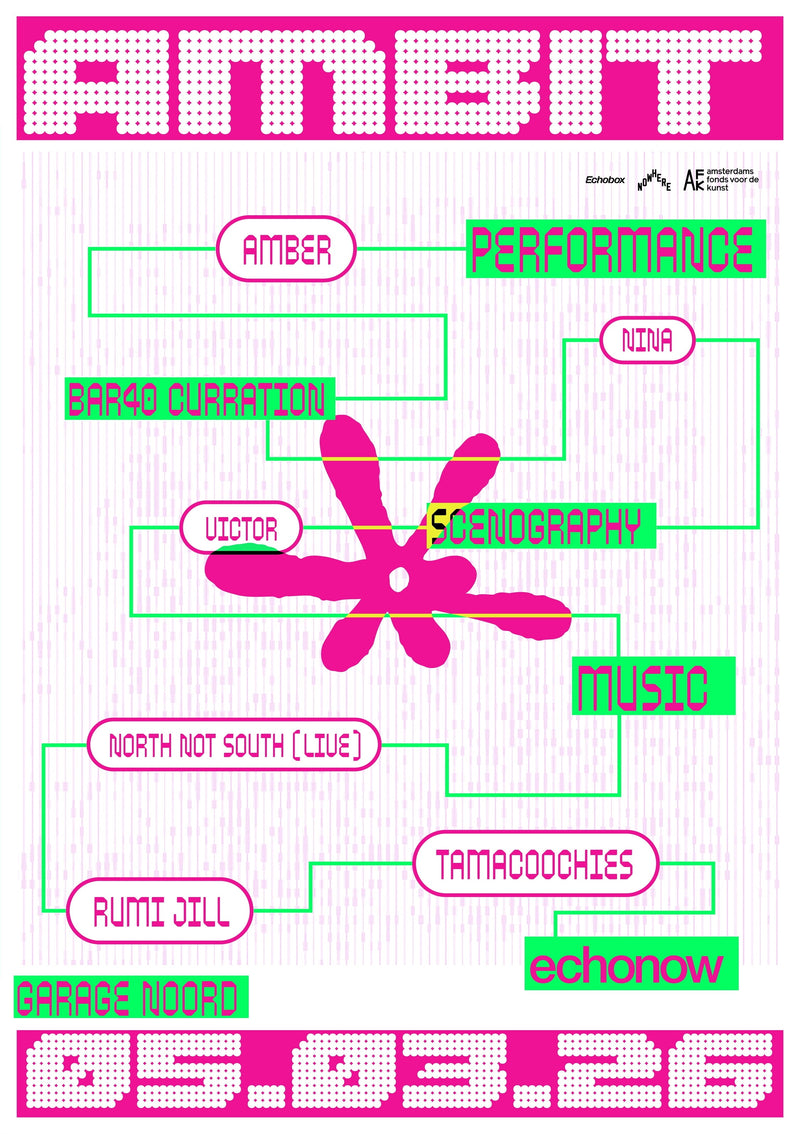

Echobox presents Echonow: AMBIT

Echobox presents Echonow: AMBIT

Young talent from Amsterdam’s nightlife scene to present at special club night in Garage Noord on March 5, made possible by AFK, Productiehuis Nowhere & Echobox Radio. On March 5, 2026, the seven young creators of Echonow, the ten-month talent development program from Echobox Radio and Productiehuis Nowhere, will present their own night at Garage Noord, titled AMBIT. This serves as the final presentation of the program in which they developed their skills across disciplines such as DJing, visual arts, producing, curation, and performance art.Launched in 2025, Echonow was designed as a comprehensive development program to give emerging talents a serious start in Amsterdam’s nightlife scene: a field that can be both challenging to access and sustain a career in. The program featured masterclasses, one-on-one coaching, and access to professional equipment. Over ten months, participants worked on their own projects under the structural guidance of key figures from Amsterdam’s nightlife ecosystem.Thanks to funding from the Amsterdam Fund for the Arts (AFK), we have been able to lower the barriers for young makers in the city. Without this support, the program would not have been possible. AFK specifically backed initiatives that help creators aged 18-27 gain access to nightlife as a cultural and artistic space.During the club night at Garage Noord, visitors will experience a full evening curated entirely by the makers themselves - featuring DJ sets, live performances, and visual art. It’s both a presentation of the results of their ten-month journey and an opportunity for the creators to introduce themselves to pioneers, curators, and others in the field.This event demonstrates how public arts funding operates in practice: how AFK resources are used to nurture new talent and strengthen a vibrant, inclusive nightlife sector. Echonow stands as a concrete success story of sustainable support for emerging creators.Tickets are available now.-

Events

-

-

Passion DEEZ for Vice

Passion DEEZ for Vice

Watch Passion DEEZ perform an exclusive live DJ set from the Vice Netherlands office. A high-energy mix showcasing signature selections.-

Music

-

-

Get Familiar: Nicole Blakk

Get Familiar: Nicole Blakk

Interview by Passion Dzenga Nicole Blakk moves like someone who’s already lived three careers. In the space of a year, she’s gone from music being “just a hobby” to a full-time reality — powered by viral freestyles, a DJ Mag nomination, and the kind of co-sign that changes how a room listens. But the most telling parts of her story aren’t the headlines; it’s the grind underneath them: 33 jobs that never fit, a sister who kept paying for studio time when nothing was landing, and a leap from Birmingham to London with £60 and zero safety net.What comes through in conversation is how intentional she is about building: letting the beat decide whether she sings or raps, getting hands-on in collaborations, and insisting every song contains a left turn — a structure switch, a language flip, a new texture. That refusal to be boxed in is also how she navigates a male-dominated industry: she doesn’t argue for space, she takes it, and lets the bars do the talking.In this interview, she breaks down the real origins of her multilingual flow — from performing French so her grandmother could feel the music, to Punjabi “shop tours” that turned student survival into a viral moment — and reframes “Money On My Mind” as more than a catchy hook: a mantra for staying focused when feelings and pressure try to pull you off course. Grounded in faith, community, and a relentless belief in her own vision, she’s stepping into 2026 with momentum — and with a clear message: she’s not here to be “good for a girl.” She’s here to be undeniable.After having such a monumental 2025 — viral freestyles, bucket list collaborations, a DJ Mag nomination — when did it start to feel real to you?It started to feel real when I met my manager, Wez Saunders. Music had always been a hobby for me. I’ve loved making music since I was young, but I studied Digital Marketing at university, did my Masters degree and kept working. I never thought music would become “a thing,” even though I wanted it — I just didn’t know how to get into it.My older sister was paying for studio sessions and music videos, and even when it wasn’t going anywhere, she still believed in me and pushed me to keep going. Then I met Wez, and within a year I was on the Glastonbury guest list performing on Shangri-La main stage, did SXSW, had the Dave feature, and DJ Mag nominations… all of that happened within a year. That’s when it became a full-time job instead of me working random jobs.What kind of jobs were you doing before music became full-time?Honestly, I’ve had 33 jobs. It sounds terrible, but I was always working on something. Hospitality, even construction — nothing ever stuck. I’d leave a job and already be looking for the next one. I just could never settle because I knew music was what I really wanted.When you started making music as a teenager, were you already making the same kind of music we hear now? Or did your sound shift while you were finding your voice?I wasn’t rapping at all back then. I was singing. I was writing poetry and singing. Rapping was new — I only started rapping about two years before I met Wez.What made you start rapping?I started rapping because I was trying to make a diss track to my ex. He was a rapper. From there, I just kept going and didn’t stop.When you’re in the studio, do you approach a track more like a songwriter or like a rapper? What comes first?The beat comes first. I listen to the instrumental, and the type of beat tells me whether I’m going to rap or sing. A lot of producers, before they even hear my stuff, will approach it like a soft guitar vibe because they see a woman and assume I’m going to sing — melodic, not bars. But I get really involved on the production side. I want my music to feel different. I always make sure there’s something different in every song — adding a language, switching the structure, putting rap in the second verse instead of the first, whatever. I feel like I’m very unique as a person, and I try to reflect that in the music. And I don’t plan what I’m going to write before I get there. I get to the studio first, feel it out, and build it from there.So it’s not just “writing over beats” — it’s more like you’re building the record with the producer.Exactly. It’s collaborative. I’m not just jumping on anything — we’re making the music with intent.You mentioned expectations people bring into the room because you’re a woman — but you’re also unapologetic and empowered. What challenges have you faced navigating such a male-dominated industry, especially in studio sessions?A hundred percent. It’s frustrating, and I know I’m not the only woman who feels this. In male-dominated spaces, it feels like you have to prove a point. If I wrote the most basic bars and rapped them, people wouldn’t react — but if a man rapped the same basic lyrics, he’d get the craziest reaction. So I have to make sure I’m doing the most: punchlines, language switches, everything.Even performing — I feel like I have to have the best stage presence, otherwise people hit you with, “She’s alright for a girl.” I heard that once and I was like: no. Don’t add “for a girl.” If I’m next to men rapping, I’m clearly as good as them.The hardest part is trusting yourself. Trusting yourself as a woman in that space can get difficult, and it’s so easy to start thinking you’re not good enough. Men naturally carry this aura of dominance, so you have to put your foot down. Now, when men come with little comments, I let my music do the talking. I’m like, “Cool — put a beat on right now.”When I listen to your music, I hear you switching languages a lot. What’s the intention behind expressing yourself in French and Punjabi?French is actually my first language. It’s the language I grew up speaking. My grandma didn’t speak English — she passed away now — but she was one of my biggest supporters. When I was younger, I’d perform covers like Nina Simone or Ben E. King, and I’d switch some verses into French so she could understand and enjoy it too. I started doing that when I was like 13 or 14, so switching languages just became natural.Punjabi is a different story. I have Indian heritage, but not from a Punjabi-speaking part of India. Punjabi came from my close friend Sana — we’ve been friends 12, 13 years — I used to spend time at her house and we listened to Punjabi music a lot. Her grandparents would talk to me in Punjabi like I understood it, so I picked up little words and phrases. It became the same idea: putting language in for people to enjoy it too. And then the TikTok moment happened.What happened?I was at university, and I ran out of bread and milk. I went to the shop and the guy working there was Indian. I said, “If I sing to you in your language, can I have this bread and milk for free?” I was serious — I had student loan coming in four days, I just needed something to last me. He agreed. My friend recorded it. It went viral on TikTok — to the point I get paid from those videos now. Other shops started inviting me, and I started doing these “shop tours” — going to Indian shops and restaurants, singing, not charging them, helping small businesses with promo, and getting free groceries. It was a win-win.Your song “Money On My Mind” feels like an anthem for manifestation and shifting your mindset. What does “wealth” look like to you beyond money?For me, wealth is love and support. I live far from my family — they’re in Watford — and after uni I got used to loneliness. I’m close with my sister and my mum, but it’s different when people are physically there. My manager and his family became a huge part of that for me — and that was before the music even took off. Holidays together, dinners, group chats, song suggestions, encouragement. They live 15 minutes away. That kind of support is richness.And my older sister has always been that. When I felt like it was pointless, she told me results don’t come straight away. I started at 13 and started seeing results at 22 — that’s 11 years of effort without much back. That was hard. But I’ve always been rich in the sense that I’ve had people who care about me. Now it’s also people online — messages every day, positive energy. I try to give that back too. My real name is Blessing-Nicole, so I try to live up to that — to be what my name says.Let’s talk about the record itself. When you made “Money On My Mind,” what were you trying to capture?I’m very empathetic — I feel what other people feel. If I see someone upset, I’ll carry it all day. And before, that could throw me off what I was doing. “Money On My Mind” captures the shift from dreaming to actually doing — when it becomes a career, not a hobby. It’s me telling myself and listeners: it’s fine to be in your feelings, but don’t let it block your bag, your goals. Stay focused even when it’s heavy.You kicked off 2026 strong — Red Bull Cypher, DJ Mag, everything. What keeps you focused as a young creative?My faith is a big one. I’m Christian, and without that… I don’t know where I’d be. Things can get hard. I left uni, lived in Birmingham because it was cheaper, then I literally had a dream I lived in London. The next day I moved to London with nothing — like £60 in my account. I lived in a shared house with seven women, didn’t unpack my bags, kept telling myself: I’m not going to live here for long. And now I’m in my own apartment.It was faith, prayer, and people around me motivating me — my sister, my manager’s family. They let me stay with them when I was struggling, took me out of the country. I didn’t even realise how weird my situation was until I got out of it. And honestly, I had tunnel vision because I had no other choice. I moved with nothing — I had to make it work.You grew up in Watford, but still made a huge push to live in London. Why was that move so necessary?I left home at 18 for uni. After my master's, I stayed in Birmingham because the rent was cheaper — I had my own apartment for about £600 a month. It was a simpler life. But I didn’t want to move back home, so I took it as a sign and moved straight to London. At the time, I regretted it — crying in the middle of the night like, why did I do this? I had an apartment and now I’m in a tiny room with strangers. But I don’t regret it. I’m glad I did it when I did. And Watford isn’t London at all. Even the transport costs show it — getting into London from Watford can cost you way more than moving around inside London.You featured on Dave’s album — that’s a huge cultural moment. What did that experience teach you about yourself as an artist?That whole experience was transformative. Even getting the call — “Dave wants you on a song” — was crazy. I grew up listening to him, and I was one of those people speculating about his album like everyone else. I didn’t think I’d be on it. That song — “Fairchild” — it felt like the full weight of the story. You can even hear me crying at one point. It’s not just a song — it’s lived reality for so many women. Dave is a master at turning self-analysis into commentary. Stepping into that perspective felt like truth.And the studio experience wasn’t just recording — the first session was three hours of talking about my journey and the music. That showed me he really cared. He didn’t just want a voice — he was intentional. It made me reflect on myself like… the fact Dave is considering me? That’s mad. It taught me that hustling has purpose — you can create something that lasts. That song feels like it could be used in schools, like it’s bigger than music. Even now, it still doesn’t feel real that I’m on a song with Dave.Did that collaboration change how people treat you in rap spaces?Yes. I’m seen differently. I get more respect now in rap spaces. I never bring it up — other people do — but it changed perception. I wish it didn’t take that to make people take me seriously, because I’ve worked hard for a long time. But I’m grateful for the opportunity to showcase myself on such an important project.Your Red Bull Cypher moments went viral — especially the Punjabi one. Did you expect that level of reaction?I expected a reaction to the Punjabi one because I was rapping “Heer” by Jags Klimax — a proper old-school Punjabi classic. It’s one of those songs you only really know if you grew up around it. As soon as I heard a Punjabi beat, I knew I had to do it. It went crazy viral — still going.And the best part is, after that video blew up, I actually went into the studio with Jags Klimax and we recorded a remix together. That was a full-circle moment.But seeing people react to me beyond the Punjabi stuff — just me as an artist — that surprised me. Red Bull really pushed me out of my comfort zone: time constraints, briefs with specific words, and freestyling about objects in front of you. I’d never done that. I started rapping to diss my ex — I didn’t think I’d be rapping about objects on camera.They also choose the beats — you don’t. So you’re forced to adapt. I loved that. It made me a better rapper and a better artist. Now if I’m given a brief, it’s not scary — I’ve done it. It boosted my confidence too. My first episode I was the only girl, so I was nervous — but in the comments, people were calling me the standout, the MVP. I’m grateful to even be picked.You’ve built momentum through platforms like DJ AG, Red Bull, and viral content. How important is radio to you — is it still something you want to pursue?I’m open to everything. Anything helps. Even if something has three listeners — you don’t know who those three people are. I didn’t know Dave was watching my Instagram; he told me he’d been looking for a while. You never know who’s watching.So I’m never closed off. If someone wants me on their platform, I’m grateful — they’ve taken time to support me and push me as an artist.Do you want to do more women-only cyphers too?Yes. I’ve done all-female cyphers — like the Steeze Factory International Women’s Day cypher coming out soon. I love working with women. Even if we get the same brief as men, we’ll write completely differently. And I feel like I bounce better with women because we have similar experiences — it feels good. I’m not closed off to rapping with men — it’s inevitable — I just have to make sure I’m better than them.Whilst Defected traditionally is associated with House Music, you are Published by Defected; how does that relationship work?My manager (Wez Saunders) is the Chairman-CEO-and-co-owner. The Publishing team help with sessions and Wez never puts me in a box. He tells me to create what I’m comfortable with. Some days I’m singing the whole time or writing ballads, some days I’m rapping on a grimy beat. We found a balance and my sound, and I wasn’t rushed.Defected Music Publishing also partners with Warner Chappell, so I’ve been to writing camps and met R&B artists, grime artists, and producers. Through this, as well as opportunities through Sony Music, I have written with house producers too. I’ve done some house toplines, but it’s unlikely I will make house music. But I’m not closed off, you never know what the future may bring.After everything you did last year — Glastonbury, SXSW, DJ AGl — are there plans for more live shows in 2026? Europe maybe?I hope so, but I don’t even know yet. I’ve mostly been recording. But I’m hoping for a similar summer to last year — probably better, because now I actually have music out. Last summer I did Shangri-La with no listeners, no releases — nothing. If I did that then, I have no doubt this summer can be big. I’ve got an amazing team.Can we expect more music in 2026?A hundred percent. I’m releasing this whole year. My first release is actually coming out tomorrow.Before we wrap, what’s the most full-circle “bucket list” moment you’ve had recently?Opening for Lady Leshurr. I grew up on her — I knew her Queen’s Speech word for word. There’s even an old video of me doing it when my mum was in hospital behind me. My whole family went to see her at a festival, and then the next year I was opening for her. She didn’t know who I was at first, but later she told me she’d been trying to find me — she kept seeing my videos but didn’t know my name. Then she asked me to open her London show and I was like… what? We have each other’s numbers now, she texts me encouragement all the time, and I still scream when she messages me. I’m still fan-girling. I keep it real.One last curveball: Arsenal. Where does that love come from?My biological dad supported Arsenal, so I had Arsenal bed sheets, pillowcases, curtains — everything. I played football for about five years — went to a school where Watford scouts footballers. After lockdown, I gained weight and stopped playing, but I’m getting back into it now — training with some girls, planning to find a team in my area.I love Arsenal, but my favourite player is Cole Palmer — which is strange because he’s not Arsenal. I hope one day he signs. I even wrote a song called “Cole Palmer” and the next day he scored a hat-trick. So… you’re welcome.With Money (On My Mind) out in the world, Nicole Blakk isn’t just building momentum — she’s setting the pace. Sharp, self-assured and completely in control of her narrative, she’s proving she belongs at the front of the UK rap conversation. And if this is the focus she’s moving with now, understand one thing: she’s only getting started.-

Get Familiar

-

-

Dreaming Whilst Black on Omroep Zwart

Dreaming Whilst Black on Omroep Zwart

The second season of Dreaming Whilst Black premieres on February 19 on Omroep ZWART and NPO Start. Omroep ZWART will also host an exclusive screening in the presence of the two leads, Adjani Salmon and Dani Mosely, to which you are invited. The sharp and layered British comedy series, co-produced with A24, follows a young Ghanaian filmmaker trying to make a career amid everyday racism and a hostile system.To celebrate the launch of the new season, Omroep ZWART is organizing an exclusive screening at the Zandkasteel in Amsterdam. For this occasion, creator and lead actor Adjani Salmon and co-star Dani Mosely will travel from London to our capital. Following the screening, there will be an informative panel with Adjani and Dani, in which they will delve deeper into the creative process, the themes of the new season, and their experiences in the film and television world. This promises to be an inspiring evening, with unique insights into the making of a successful, international series. This event is organised in collaboration with our partners: Volkshotel, Patta, WhatsCulture, The Black Archives, and the NPO.In the new season of Dreaming Whilst Black, Kwabena lands his first directing gig on a television series called Sin and Subterfuge. Pressured by actors' egos on set and the commercial demands of executive producers, Kwabena increasingly finds himself at odds with his own ambitions and insecurities as a creator. Meanwhile, Maurice and Funmi navigate life with their newborn, and the arrival of Amy's sister adds to the dynamic. This season further delves into Kwabena's personal relationships and places his professional ambitions within a broader Black-British context. All of this is done with the same humor and warmth that made the first season so successful.Dreaming Whilst Black combines humour with sharp observations about systems and identity, as Kwabena continually clashes with expectations from his own environment.Stream season two of Dreaming Whilst Black from February 19th on NPO Start.-

Art

-